A Fine Dessert becomes A Fine Mess

If you’re active on Twitter, Facebook or some of the children’s literature blogs, you’re probably aware of the controversy involving A Fine Dessert: Four Centuries, Four Families, One Delicious Treat written by Emily Jenkins and Illustrated by Sophie Blackall. (Schwartz and Wade, 2015)

I first became aware of the controversial aspects of the book in August when Debbie Reese Facebooked about problems she was finding in one of the images. Only recently did I actually pick up the book so that I could see what everyone was talking about. I took a very different approach by not reading the text. Because the book is being talked about as if it could be a Caldecott contender, I opted to read the images.

Have you read the book? As indicated in the title, it’s the story of families over time enjoying the same dessert. It takes on a rhythmic appropriate for 4-8 year olds, but it’s that rhythm that I think causes the books problems. That rhythm of these families creates a likeness that is only true if you think living in America makes us all basically the same, trying to find commonalities in European and African American history. Well, let’s take a look.

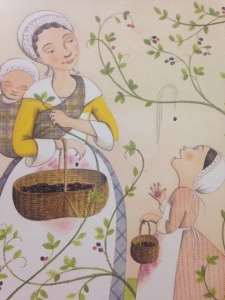

One of the first images is of this young white family (sans father) and the young girl is looking up to her mother as they pick blackberries.

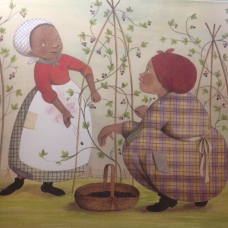

This is in opposition to s similar image where the young enslaved girl is looking down at her own mother (we know this is her mother because it’s stated in the text.)

The mother seems to have a look on her face that is hopeful at the least, happy at most.

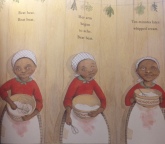

The likenesses of these individuals is certainly troubling. The same round faces, very similar clothing and even similar expressions that indicate similarity in their social and economic positions.

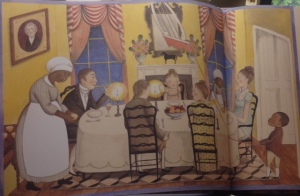

I think this is one of the most interesting images in the book because the artist conveys so much meaning. Look at those patriotic drapes. See the patriarch on the wall looking over his family? The father at the head of the table, leaning in? Such power there while at the other end of the table, the mother is demur and almost disengaged. The enslaved workers eyes are downcast and the mother is in a pose as if she is offering so, so much to this family that is not her own.

At the edge of these pages, the mother and daughter slip off to sneak some of the dessert for themselves.

Would not a 4-8 year old see the fun in hiding in a closet with their mother, rather than the dehumanizing fact that this cupboard offers the child more protection than her mother ever could?

Looking at these girls licking the spoons, can you even tell for sure which is White and which is Black?

Oh, and there’s the kumbaya moment at the end.

I admit to fumbling with this one for a moment. That rhythm is so alluring! But, I knew I’d never buy this book for my children or grandchildren. And, when I wondered how an African American would have done this book, I know they wouldn’t have. That realization make me dig deeper, have a conversation and get the nuances. I looked again, and yes pictures do speak a thousand words. Most of my problems with the book are not the same as what others have seen, yet we’re all seeing issues.

The author, Emily Jenkins has realized and admitted the book’s shortcomings and has decided to donate all her earnings to We Need Diverse Books. That, my friends, is a big deal. That is a HUGE indication that there is a problem with the book. I’ve read several things Jenkins has written and I do think she’s an ally to diversity. Diversity work is relentless! The revelations about how we reduce others, how we limit their power is continual. We have to admit how we do it on a personal level, accept the shame in that and also recognize how it’s done on an institutional level. There is no switch to turn that makes you a diversity worker one day, but not the next. Heck, I’ve even admitted that it took me a minute with this book.

Maybe you have to keep struggling with this one. Maybe you know there must be a problem because so many (INCLUDING THE AUTHOR) say there is a problem. Keep listen, keep looking. That white light is blinding and it can be hard to see through it at first.

And yes, Varian Johnson will buy the book and will read it to his girls. Varian will not read the book to his girls in the same way most white readers will read the book. He will see all the flaws in the text and images and he will know his girls well enough to know what they’re ready to discuss. Varian clearly has very high expectations for his daughters as he is preparing them with a well curated education. They will know the fullness of American history (not just the white version) and they’ll be able to read messages conveyed in text and in images. They will understand how authors and artists try to position readers, how they use their power to frame their message. Most in kidlit have said they’re saving these lessons for older students. We have to know our audience as well as ourselves when we’re having these sessions in critical literacy. Do we really see what messages are conveyed here?

Do you really see the messages conveyed?

Did you realize this post is not contextualized, that I have not linked to any of the posts containing historical evidence of the conversations and confessions relating to the book? As the owner if this blog, I used my privilege to frame this message to fit my world. That’s what people in power do. I use my power to fight the good fight.

I love you!!! thank you for all you do!! >

LikeLike

Excellent, Edi, absolutely Excellent! Adding a link to my growing list of links, and sharing.

LikeLike

Amazing work, Edi! Your clear, thoughtful analysis adds so much to this discussion.

And thank you for giving Emily Jenkins her props. She created what she thought was a good thing, she listened as people called her out, she apologized without making excuses, and she paid reparations. I totally agree with you that she’s an ally to diversity.

LikeLike

Fabulous. Thank you for this.

LikeLike

Thank you for offering this perspective, looking at the illustrations and exploring how and why they’re problematic. And kudos to Emily Jenkins! Writers depend so much on editors to help get things right, and the WNDB internship program will bring diverse editors and other publishing professionals into the process who can catch these problems before it’s too late.

LikeLike

Lyn, I too felt her editor let her down. There is so much work to do.

LikeLike

My concern is that the attacks took a personal turn against the author and the illustrator when in fact, it was a failure on many fronts. I lay some of that blame at the feet of the editorial and art direction staff. If one wanted to show some flavor of African American life – there were, in fact, free people living in those segregated times and we wouldn’t have had to address what was a controversial – and poorly handled depiction.

But I also worry about pushing for solutions that set a dangerous precedent.

1. That the content creator was embarrassed and maligned in social media to the point where she felt compelled to donate all her proceeds. Will this be the new standard? Get it wrong – pay up?

2. That the push is to “hire” new editors rather than demand publishers hire back all of the experienced people of color they let go over the years. That those editors and art directors got no support in their jobs during the pre-Diversity days was the issue. We need them to be the ones training the newer editors, not new editors being trained by staffs that aren’t skilled in diversity yet.

3. That while I appreciate the number of people who have tried to talk about this issue – I worry about the number of non-African Americans taking up the charge, rather than asking and blogging about the opinions of African American professionals who found the material problematic and why.

The problem with the new diversity push is that we talk “at” each other and not with each other. That social media has become the platform for public shaming, rather than public dialogue.

The slave depiction was poorly executed, but not the end of the world. But it could have been a great platform for starting a discussion about why publishing didn’t spot and fix this during book creation. What is happening instead is that there is a chill in the atmosphere as people grapple about how to include diversity without offending someone. And invariably, I have colleagues who consult with experts only to be victimized because the new strategy is to a shoot first, then ask questions later.

Dialogue is key. There is no black or white rules for diversity – just shades of grey and children/readers at the other end of the rainbow who deserve so much more consideration than we give them.

I hope we can find pathways back to working as a team. That’s the profession I remember wanting to devote my life to.

LikeLike

Thanks for such a thoughtful response ChristineTB, one of the best I’ve read.

LikeLike

Christine and Debbie, you’ve provided a lot to think about and discuss.

Cristine, I think one of your main points is that the author should not take the brunt of the blame and I totally agree with that. Let’s start the blame with the textbooks that call enslaved people ‘immigrants’ and the teachers who don’t catch the error. We don’t learn our own American History. What about the parents who aren’t demanding books that better represent their children? And yes, the editors who didn’t catch in and the majority white publishing houses have part of the blame. Is it enough to say anyone who doesn’t speak up against the prevalence of white culture in our society is to blame? Yes, that’s a lot, but it puts the simple fight for books written by NA/AOC and LGBTQ authors into perspective.

For marginalized people to have the platform that Twitter, FB, Snapchat and blogs provide is critical in fighting this fight. No, these platforms aren’t perfect, but they provide a voice. On Twitter, someone will retweet a cute 140 character line simply because of its cuteness without knowing the minefield they’ve just stepped inot while blogs give us didactic statements that don’t reflect an exchange of ideas. Does this result in bullying? I don’t think so. Not when Native Americans and people of color are finally having a voice, finally able to speak up and be heard. Bullying is direct, intentional and personal. What I saw did not fit this description. I saw an author simply trying to find a way to right a wrong.

How do we get meaningful dialog when the word ‘diversity’ empties most of the room? That team you mention, Christine, is critical. We do need to dialog with each other, Black, White, Latino, LGBTQIA, Native American, Asian and disabled and we need to step up for each other because it’s wearing. To our very soul, it is wearing.

LikeLike

Daniel Jose Older loaded a video of the panel he was on with Qualls and Blackall on Saturday. In it he talked about the community of people who work on a book. I like his use of “community” because it communicates a lot of nuance that “editorial team” or the like does. Part of that nuance is the segregated nature of publishing–how white it is–is a lot like what we know to be the case with neighborhoods.

Christine’s “not the end of the world” is, I think, apt. It may mean the end of a world in which a community of people involved in the production of a book like A FINE DESSERT doesn’t do that kind of book again. That’s a good outcome! A chill, too, is good. People are hitting the pause button to think about what they’re doing.

None of this, of course, is new.

This is just the current cycle of this very old conversation where people of marginalized populations engage with book creators about the ways books depict our people, history, cultures, stories. This cycle, however, is driven by Social Media. Like Edi’s blog. And mine.

Through them and via Twitter, more people than ever are part of the conversations in children’s literature, and that, too, is a good thing, because people (like me) can say “hey–I don’t like the misrepresentation you did here!” And people will read that objection. Some will pause, and read more, and then say ‘oh, I get it’ and walk away knowing more than they did before. Some will be angry and hurt and not pause to reflect on what they did wrong. Some will scream “but it is fiction!” and “quit bullying me!” and the like. I understand authors/illustrators feel shamed, but their work is for children who endure shame in the classroom. Don Tate references that in the note for POET.

It has been very terse for a couple of years now, and my hope is that we won’t go back to same-old misrepresentations. That won’t happen overnight but I think change is coming.

LikeLike

Very interesting analysis, Edi. Excellent reminder to all readers to read the illustrations along with the text. I’m not sure, however, if there isn’t a rush to judgement (and apology by the author) on this book. Thinking about how a purpose, goal, and tactic of those involved in the crime of slavery was to dehumanize the human beings they kidnaped, worked unmercifully, punished in brutal ways, and bought and sold in markets, I can’t help but cheer each time I see/read of an enslaved human being rising above the power of these acts. A little girl smiling in the presence of her mother is an important image. And, as the blackberry picking panel and the closet scene underlines, the brutality of slavery these victims suffered did not crush their humanity. As black folklore truth puts it, this mother and this child, “had one face for the master and one face that is mine.”

At least these are some of my thoughts, Edi. I’ve been retired from the ISU History Department for fifteen years. Keep up the good work of making our library and deep reading a central cog in all students’ education.

LikeLike

Hi Gary,

I’m quite impressed by the ISU History department of course because of the depth on knowledge but particularly because of the hard work they do to engage students in the study of their subject area. It means a lot to hear from a local colleague. I think you really bring home the need for approaching this from a critlcal literacy stand point. You can appreciate this book in so many ways because of what your bring to this book, your attitudes as much as you professional training. Not everyone can see the spoon licking as an subversive act, a sign of cunning and intelligence on part of the enslaved person. Many will see it as portraying slaves who were quite content in their positions and their afraid this mythology is being portrayed to another generation.

Editors, writers, educators and illustrators have to begin to realize that only 52% of the children in America are White. When books are created that don’t consider the perspective of the 48%, then there will be an outcry.We have to consider what readers bring to the reading experience. Not all bring a white reading perspective. Hopefully at some point in the reaction to books. there will be academics and scholars who join in to take advantage of the opportunity for learning. These outcries can become more productive experiences.

Me, I’d like to see these discussions, these books on enslavement move from books for 4-8 year olds to adult books. One problem this author had was that she couldn’t fully explore enslavement in this books both because of space and the age of her readers. I have to agree with Daniel Jose Older who said if you can’t do it fully, then don’t do it. Unfortunately, the concept of the fragility of slavery continues through high school. As a result. slavery is not taught well in schools. I’d really like to see more books, move TV and movies that fully explore this time in our history because until we understand and and can fully discuss slavery, we’ll never overcome racism.

And, I know this is more than a response to your comment. I’m sorry! I read what you stated last night and I continued to think about it. Please, stop by and say hello next time you’re in the library.

LikeLike

Thanks for your thoughtful reply, Edi. Looking forward to meeting you.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing, Edi. This is really thoughtful and I’m learning so much.

LikeLike

[…] of a Slave – Excerpt: Edi Campbell, a reference librarian at Indiana State University who blogs about children’s literature, credited Ms. Jenkins and Ms. Blackall with admirable intentions, […]

LikeLike